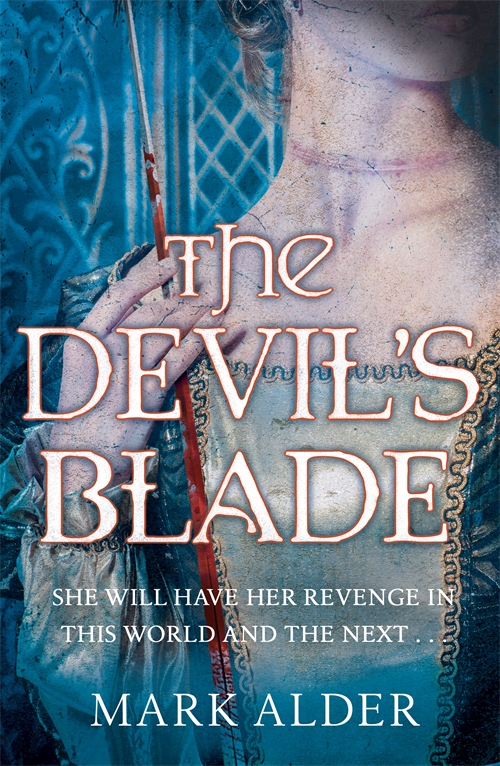

The Devil’s Blade: Exclusive Extract

The Devil’s Blade is available to pre-order now. Get it here.

Act One

Scene One

The Chorus of the Diaboliques

The torchlight is yet distant as she steps from the coach. The carriage they sent to fetch her has creaked and jumped its way over the potholes of the cinder road from the east gate to the woods and then rattled along a little track to stop here.

She kisses her companion Paval to mark an end to their fun. He is a nice boy who she met in her fruitless quest for an audition at the Grand Opera. He is the attendant on the stage door, running errands for Arcand, the stage manager. If she is to sleep her way to the top, she has joked, she has left herself a long haul from these beginnings. Still, sometimes the long road is the most enjoyable and Paval is a dear.

Paval buttons his breeches as she exits the coach into the cold of the foggy night. She lifts her doe mask on its stick to her face, shifting her weight on her feet to stop her shoes sinking into the mud. These are her only pair and she is mortally afraid of marking them.

‘Over there,’ says the coachman. ‘A footman will fetch you.’

Paval is next to her now, searching for her hand, but she dismisses it. ‘Wait here,’ she says. ‘This is high company.’

He nods, smiles his big grin.

‘So many mistakes to make with these aristos!’ he says. ‘Best have only one of us making them.’

She kisses him once more, deeply, and he takes her head in his hands.

‘I love you,’ he says. ‘Don’t do that,’ she says. ‘Why not?’

‘I am not made for it,’ she says. She almost believes it. Her plans don’t involve love for a long time yet. And yet, and yet, Paval is so kind and so warm. Could she love him? Perhaps, in a way she never thought she could love a mere man, but she must try not to. Men, to her, have always seemed too uncomplicated, too simple to love. You get things from men – money, position, names, and the centre of their souls that lies in their breeches. You share things with women, who are far more complex and interesting. Yet these simple qualities are what she has come to admire in Paval.

There is something else, though, that makes her warn Paval away. She has always felt somewhat, she cannot quite put her finger on it, somewhat, well, dangerous, for want of a better word. Her life is to be an opera, a grand work, and lovers never fare well in those.

‘You want the audience to love you.’

‘That is a different kind of love,’ she says. ‘You are a love, Paval.’

‘I know you only hold back from me to lead me on.’ ‘Was I holding back in the carriage?’

He blushes, sweet boy. ‘Not like that.’

‘Then like what?’ She comes close to him, still careful of her shoes in the mud, gives his dick a squeeze as she lowers her mask.

‘I’ve forgotten,’ he says, close by her mouth. ‘Well, tug on that until you remember,’ she says.

A light cough from behind her like one of a lady’s more demure spaniels suggesting it might like another biscuit.

She turns. A tripping servant, wigged, powdered, heavy with satin bows, comes towards her and takes her hand to lead her. She doesn’t really like that. She knows she is only the same station as he and that it is no affront to be led this way, but she does not want to appear as his equal among the great men she is to meet. One day, after her singing career is done, perhaps before, she will be a duchess. Julie may have been born poor but she will die rich, whatever it takes.

She rejects the man’s hand, gives him a look. ‘Suit yourself, dear,’ he says and heads off up the track into the deeper woods. She collects herself, stands straight to her considerable height and strides following him along the track, humming a few scales under her breath. That is all she has ever needed for a warm-up. She was born to sing, born singing if you listen to her father, and she has been singing all her life. Warm up? Her lovers say she sings in her sleep and she has had enough of them to make a reliable jury.

The wet smell of autumn chills her, the track is slippy and she does her best to retain a good bearing as she walks along it. Head up, shoulders back, as if she is about to burst into song. She commands the stage of her imagination as she is sure she will one day command the stage at the grand opera. These gentlemen she is to meet – the Tredecim as the group of patrons style themselves – are the gatekeepers of her future. She is met in a clearing by a group of four men who bear lanterns that make soft webs of light in the foggy air. They are masked, as is the fashion at soirées and balls. The theme they have chosen is unusual – the masks are all in the style of devils. She does not find it disconcerting. This is the high society to which she aspires. Masks, feathers, stomachers trimmed with gold and silver braid, emeralds, diamonds, rubies, things she has glimpsed as they flit between carriages and the gilded interiors she peeked into as a child.

Instinctively, she knows what she must give these men. The Comte’s sons, before they went up to court, were as dirty, flea ridden and naive as she was but she has learned enough from the men those boys became when they returned from court, and later from war, to understand them, at least a little. They do not have the sentimental tastes of the bourgeoisie – they favour the disturbing, the elegant, the challenging. It is here she will learn to belong.

The gentleman devil who takes her arm to lead her further through the trees is perfumed with a rare violet scent and wears a coat of the silvered cloth they call Gros de Naples – a lustrous silk inlaid with crimson half-moons. She has seen this cloth before only outside dressmakers as it is delivered and, yes, she makes it her business to haunt such places to know better how to furnish her dreams. Here, conjured from its long slumber on the roll, bid to rise and take life as a coat, the cloth transforms its wearer into a fabulous animal, a shimmering leopard who leads her to the magnificent Court of the Beasts.

And what a court. Twelve more men, all masked as devils, stand in a circle, each one a statue raised in tribute to excess, self-love, love of life. The torchlight makes deep pools in brilliant silk coats, glints from buckles and rings, turns the milled brass of a cane tip – shaped as a toad – to fire. It glitters from the jewels of the masks, sparkles from the gilded hilts and scabbards of their fine slim court swords. These are gentlemen and they wear the latest weapons – short and slender blades, no lumbering long rapiers here, like the ones her father taught her to fence with. She tries to distinguish the men in some way for, if she meets them again, she could use this connection to her advantage. One has roses on his shoes, another an emerald ring that glints green even in the red light, one more has an uneven stance, one leg shorter than the other, another has the monograph of a hart upon his coat, still one more pats his friend’s back and says, ‘Courage, Diablo!’ Is that a name or a nickname?

One of the men in the circle speaks. ‘This is the virgin?’ A voice, old and dry with vowels so strange and clipped that Julie has to suppress a giggle. He sounds like a comic actor aping a nobleman, rather than a nobleman true.

The speaker is tall and stands with one foot forward, a hand on his hip as if posing for a portrait. He wears a coat of blue silk inlaid with gold. The hand that supports his cane, Julie notices, has two fingers missing. So a duellist, or a warrior. No wars for a couple of years now. He must be bored, poor lamb, she thinks. A man like that needs action. She wonders what it would be like to lie with him. Would he just strike poses while she did all the work? She smiles to herself. She knows a few tricks to rattle an icy composure but she would get nothing back from him, she is sure. And so what? In lifting her skirts for a man like that she’d be after so much more than a tremble and an ‘oh!’. She’d be seeking a destiny.

‘This is the street singer,’ says another man, his voice equally mannered. It is as if he has made scissors of his lips and is trying to clip and trim the words as they emerge. Not that she can see his lips. His face is only that of a leering devil, horns and long nose, a painted mouth of teeth.

The first man lifts his hand to his mask.

‘Let her sing,’ he says. ‘And let us see if she is, as you claim, Abaddon, God’s creation.’

The man raises his hand. A splendidly dressed servant in a powdered wig turns to a servant who is merely impressively dressed and raises a finger. That servant turns to a servant who is well dressed and he to another who is certainly no scruff and raises a finger. This servant turns to her and raises a finger of his own.

‘Now?’ says Julie.

The unscruffy servant nods.

‘Well, by God’s bollocks,’ says Julie. ‘You might have just said so yourself!’ Oh no. Nerves, the masks, the night, the fog have conspired to make her forget herself.

‘God’s bollocks?’ says one of the devils. He carries a stick of silver and prods it forwards as if the words are on the ground before him and he is jabbing them to inspect them.

‘Begging your pardon, it is an expression we use when we are . . .’

The three-fingered gentleman inclines his head. ‘Who are “we”?’

‘The people.’

‘The word “we” should be outlawed,’ he says. ‘There is no “we” wide enough to pair me with the likes of you and the mob.’

‘Oh do fuck off,’ says Julie. Oh no! The nerves again. They have betrayed her. She wants to smile and nod and be pretty but from somewhere this defiance has emerged. She curtsies. ‘Begging your pardon, sir. I am inclined to such outbursts when nervous. Think naught of them.’ Do they say ‘naught’ for ‘nothing’? She hopes so and hopes it might make her seem more refined.

He inclines his head, studies her as a cat might a spider. ‘She’s a mite coarser than one might have assumed, Diablo.’ ‘Her singing bears no mark of it,’ says one of the masked devils.

Three Fingers raises his hand again and the chain of command ensures a much lower status hand is raised in front of her to tell her to sing. Well, she’ll take the evening so far as a success. She has never spoken directly to such a great man before, even if she did tell him to fuck himself.

She imagines herself his wife, he away hunting or at war, or poking about in the woods dressed as a devil, she at the opera, singing in his jewels, in the dresses he might buy, riding home in his gilded carriage, riding the grooms, riding the maids, giving the tall, thin duke some bonny fat children he would have to call his own or face dishonour. She sees herself in black, at Versailles, looking out at the fabled lawns, loudly cursing the Spanish or English or whoever’s ball of lead so conveniently killed him and left her a rich widow. She would be comforted by some gorgeous duchess, yes, a widow too and she would fall in love and be loved. She could fuck a man, she could laugh and play and be ever so fond of a man, but she could only ever really love a woman – this fantasy duchess with her hair in a tower of stolen curls, a shepherd’s crook of gold in her hand, little tame lambs in diamond collars to wander behind. Yes, she could love a woman like that madly. Perhaps Paval might be there too, as her secret, or not her secret. He could fuck one woman well enough, why not two?

She would commission arias just for herself and sing to the golden angels on the ceiling of the Opéra so well those angels would think she was one of them. She has not seen Three Fingers’ face, but already she has married him, killed him and is spending his money becoming – what? Great. Yes, great, grand and beautiful. She is already pretty but she wants something more, to have an awing beauty that makes the world her slave. All love, to give and receive love magnificently. Yes, she will become the world’s lover and be loved by it in a mad amour that will lift her to the heavens. Well, a girl can dream, can’t she?

She clears her throat and begins. These great men will not be charmed by sweetness or by coyness the way a street crowd would. For them, something more sharp, piquant, more challenging. She must sing of love, though, and everything that goes with it. She must stir their blood, stiffen their pricks and then they are hers and she can get what she wants from them. She dismisses the song she was going to sing. Instead she will sing one she heard not weeks ago after Paval smuggled her in to the Opéra. She only needs to hear such things once and then they are lodged in her mind. She will sing ‘The blood that unites me with you’, from Lully’s great work Armide. And she will sing both the part of Armide the enchantress and her lover Hidarot, her range great enough to accommodate both.

She doesn’t need the note, doesn’t need the harpsichord to bounce her in. She begins and the wood holds it breath. No bird has ever sung like this, no footpad trilled or whore hummed in such a tone. It is as if something new and strange is being made, coming to birth in the world. A night flower unfurls and offers its inky petals to the moon. Probably, anyway. Somewhere that must be happening, she thinks. She sings of it, which is how the song begins. The gentlemen are statues. Only one paws at the air with his hand as if it is floating on the melody.

She allows a brief silence when the low part is finished, to create a tension, spark desire through denial. And then, and then, Armide herself. She begins. Unaccompanied, there is no wavering, no guess for the note. Can any of the gentlemen believe she has never been trained beyond what a country estate had to offer her? They cannot.

The notes tumble from her, so pure, so clear and delicious in the still air of the foggy wood. The conclusion, when it comes, seems torn from her soul.

‘Against my enemies at will I unleash The dark empire of Hell;

Love puts kings under my spell,

I am the sovereign mistress of a thousand lovers. But my greatest happiness

Is to be mistress of my own heart.’

They are enraptured. They are entranced. There is a long silence. No one speaks, as if the merest chance that this flat fog, these damp trees, might offer an echo of the song’s magnificence.

‘Truly a creation of God,’ says Three Fingers. ‘A rare talent indeed.’

‘Mwah!’ One man makes a kissing gesture to his fingers before snapping them out before him in approval.

Another devil just nods furiously before taking out an over- large snuff box decorated with a dragon, pinching out a mighty nip, shoving it beneath his mask and inhaling it with a snort of delight. She sees a gobful of dark teeth as he casts back his head and the snuff goes in, a sure sign of wealth. They say it’s sugar that makes the teeth go rotten and who but the very well off can afford that?

Julie’s heart skips. With patrons such as these, what things might she aspire to? There would be no limit to her ambition. She sees herself on stage at the Opéra, bathed in candlelight, filling that great space with the music that flows through her. ‘A virginal flower,’ says another, a fat man who carries a gilded, finely wrought pistol in his belt.

‘Let us do what we came for,’ says a tall, thin man who waves a pristine white handkerchief. ‘Let us sacrifice her and call forward the Devil. It is your turn to lead, Bissy,’ he says to the little fat man.

‘Sirs?’ says Julie. She doesn’t understand, not at all. Sacrifice? What does that mean? If you wrote those words down, passed them to her and asked her to read, she would know what was meant. But there in the wood, they come as such a shock that she cannot make sense of them.

Swords are drawn, the blades shining tongues of fire. Now the words make sense, terrible sense. Julie feels her stomach fall to her feet as she knows she is the victim of an awful trick. She pulls out her hairpin – useless of course against these blades – but she will not go down without some sort of fight.

A snort of laughter from behind the masks.

‘Beelzebub, we have paved the way,’ says Three Fingers. ‘We have spoken your names, we walked the circle widdershins, we have cursed God and his angels!’

‘We spit on the name of Jesus!’ shout the men.

‘We praise the names of Judas and of Satan and of the great Whore of Babylon!’ shouts Three Fingers.

‘We praise the Whore!’ the men chorus.

They close in on her like wolves upon a stricken deer, pacing forward slowly, confident their prey cannot escape, their dead-eyed masks fixing her with lethal stares.

‘Take the virgin!’ says Three Fingers.

‘I am no fucking virgin!’ screams Julie. The men pause, as if partway through a dance whose music has frozen.

‘What?’ says the man with the scissored vowels. ‘I am no virgin!’

The masks turn to each other.

‘You are a country girl of sixteen,’ says a man who twirls his sword as if he is an idle lover twiddling a stalk of grass at a girl’s gate.

‘And I have not been a virgin these two years!’ says Julie. ‘Sirs, if you seek to kill a pure woman, you will not find one here. There is little to do in the countryside but horizontal pursuits and, once the love of that pastime is secured, there is very little that can shake its habit. Why, the Comte d’Armagnac fucked me himself on my fourteenth birthday and I was glad to have him!’ This is not quite true. The Comte had dragged her to his bed, but he had been so drunk he fell unconscious when he got her there.

‘You are merely trying to save your skin. You are an untouched girl. You country women save yourselves all for one sweating oaf, I know,’ Three Fingers says.

‘I don’t know,’ says one devil. ‘They are at it like dogs from as soon as they are able in my estates in Évreux. With me quite often.’

‘I had a man not half an hour ago,’ says Julie. ‘In the carriage that brought me here.’

‘In the carriage here?’

‘I was nervous. You know what they say, sirs, “a fuck for luck”.’

‘They?’

‘The people. Or rather I do. The act is very calming, sirs, and I do believe it enhances the female voice! I sing so well for a reason, sirs, think of that. The contact with men enables my low notes, I am sure of it!’ Her heart is racing. She is speaking the words, but it is as if she is outside her body, looking in. She did not come here to die. She has so much, so much, to do.

‘Is the carriage still here?’ says Three Fingers.

‘It is,’ says a man in a coat adorned with butterflies. ‘At a distance, with the servants.’

‘Go and see if the groom is there.’

‘Why don’t we kill her anyway?’ says another devil.

‘It’s a matter of how, not when. I’ve another two hundred lines of summoning to get through before we’re meant to kill her,’ says Three Fingers. ‘I can save a lot of effort if I know it will come to no good.’

A devil lifts his mask, takes a nip from a bottle of brandy. She sees his face briefly, an eyepatch on his right eye, a mess of scars beneath.

‘Are we required to fuck her for this ceremony?’ asks another devil.

‘Yes.’

‘But not if she’s a strumpet, right? My syphilis has gone away, and I don’t want it back. I will only fuck virgins and my wife, you know that, dear boy.’

‘No need to fuck her, we just kill her.’

‘Excellent. I’ve just had these breeches made by Daquin. I don’t want them stained with mud,’ says another voice.

She hears a cry from the trees: ‘get off me!’ and realises, with alarm, that it’s Paval. What will these men do to him? If she is to die, must he? She has placed him in great danger and must protect him. He is prodded in at the point of a sword. ‘Paval, I lied and said we had fucked in the carriage. Deny it. Sirs, I am a virgin, I admit.’

‘Too late,’ says the devil with Paval. ‘He has confessed it already. Twice in the carriage and many times before, it seems.’ ‘Oh, in the name of Satan, Villepin, do you not check these things before dragging us to the woods for nothing?’ She cannot tell who is speaking beneath the masks.

‘Bring wine,’ says Three Fingers, loudly to the darkness.

Swords are sheathed and the servants bring wine. One of the devils leers at Paval, says ‘boo!’ and the boy shrinks away, terrified. She must do something.

‘Would you like another song, sirs?’ she says. All her life she has been able to charm with song.

‘A swansong, why not?’ says a devil and she does not know what he means.

Paval is glancing from mask to mask but the devil who grips him still has his sword drawn.

‘And if I sing well enough, will you let us go?’

‘I might keep you as a servant,’ says Three Fingers. ‘Who knows?’

‘And my friend.’

No one says anything. There is no sound in the woods. The fog muffles everything to silence.

Begging will not help her. She knows these to be proud men who expect and respect pride, courage and arrogance. And so she sings, one of Lully’s death songs.

‘Shades, ghosts, companions of death,

I do not ask of you, I do not want mercy.

I do not complain of this my lot,

This exchange I do not call cruel.

Shades, ghosts, companions of death,

Let not such just piety offend you.

An unknown force that I feel in my breast Gives me courage, spurs me on to the test, Makes me greater than myself.’

She lets the words babble from her, sweet as a brook, and then burst out, cold and pure as a spring torrent. The men stand rapt, masks tipped back just enough to allow them to drink the offerings their servants bring, sipping brandy from crystal glasses. All the time they never take their eyes from her. She sings, sings for her life, for Paval’s life. She goes on from the song to the whole opera, every part, effortlessly transposing the key of the lower parts as the men drink. While she is singing, she is not dying. She does not stumble on the words, nor the tune. Such things imprint upon her and need no memorising, no work to hold them. She lets the music flow through her as the night grows colder and the men drink, do nothing but drink, their masks tipped back, easy in their command, their control of Paval and of her. Paval is terrified, shaking. She cannot run, in her silly shoes and skirts, but Paval can and she wants him to, but he is there for her and will not leave her.

‘I warned you not to love me,’ she thinks. ‘And now see the good it has done you. Paval, don’t share this fate.’

She does not drink – of course, she is not offered a drink – not beer, not water, not brandy and after two hours, maybe more, it happens. She has sung almost every part, transposed and moved up a register here, down here, but every part. Her voice cracks and the spell is broken.

The chief devil, Three Fingers, shakes himself. ‘Enchanting,’ he says. ‘Quite enchanting.’

He walks up to her, his eyes black pits in his leering mask, and inspects her as one might a work of art. The blow sparks white light in her head, sends her to the earth as if all the bones were knocked out of her. She hits the ground like a fish smacked onto a slab. He has punched her, she realises, hard in the face.

‘Fuck her!’ shouts someone. Paval screams. She looks up. A devil grips him from behind and draws a knife across his throat. Paval falls, a wound like another great mouth at his throat. ‘Paval, Paval!’ she cries out.

She is kicked, punched, two devils have her, but she bites, kicks and is free. Her head is spinning with the force of the blows, but she fights to regain her senses, blinking, gulping in air.

‘Bitch!’

Another – this one in a much plainer mask than the rest – lunges for her but the music is in her; she is a dancer turning aside and letting him stumble over a root, so he lands heavily on his knees.

‘My silks! My silks!’ he cries out, but she steps in behind him and draws his sword from his scabbard.

‘You will leave me, sirs!’ Her heart is pounding. Paval! Is he dead?

‘Montfaucon, you fool,’ says a voice, ‘you let a girl take your weapon. We should never have had you along as a prospect!’ Three Fingers approaches. She looks up at him. Her senses are scrambled, and he is like a creature from a dream, blurred, an assembly of colours, a wavering flame himself among wavering flames. She is going to black out, wants to black out.

‘My father taught me the art of defence, sir,’ she says. ‘You’ll not find me easy with a sword.’ She thinks of her father now. He blessed her as she left to go into the world, thought it a wonderful thing she sought to carry her gifts to the highest stage in Paris. He had always known she would go, he said, right from the time she was small. But he had put a sword in her hand early, taught her the arts of defence because he knew that a lone woman in the world of Paris would need such a thing.

Three Fingers laughs a little laugh, puts his fingers to the lips of his mask like a maiden aunt hearing a saucy story. ‘This is the best swordsman in France!’ says a mocking voice from behind him.

Three Fingers flashes his sword like a whip, through the torchlight.

‘If in France, then in the world!’ says Three Fingers. ‘Put up. Fellows, stand back.’

She points the sword at him, in line, as her father had told her, arm straight, the point as far from her body as it can be held. Whoever wants to kill her will have to deal with that first.

‘Oh dear,’ says Three Fingers. ‘Oh dearie dear.’

He steps in and, with a squeeze of his fingers, he has beaten the blade aside, extending his arm to offer the merest snick on the fabric of her sleeve with the tip of his blade.

‘I can take your weapon and make it mine!’ he says, encircling her blade with his so it feels it will spin from her fingers.

She regains her grip, straight arm quivering. ‘I can oppose you, steel to steel!’

He shoves his sword forward, angling the hilt wider to deflect her blade, using it to guide his point to its target. Another snick on the sleeve. Her arm is cut, and she cries out in pain. ‘I can ensnare the blade!’ he says. ‘Bind and cross, transport and deflect, make your arm my arm and move it where I like!’

In a whirl he has caught her sword with his and moves it at will.

‘A straight arm is a fine defence against a village thug!’ he says. ‘For me, it is a gift! And I give you my best gift in return. Without crosspiece or blade breaker, with no dagger, buckler or cloak but with only fingers and wrist, I give you the disarm!’

In a flick her sword is out of her hand and flashing through the torchlight.

She steps away but he has trodden on her foot and, unbalanced, she falls to the ground.

He has the tip of his sword at her breast and she cannot move at all.

‘Had I the surgeon’s art,’ he said, ‘I would cut your throat so nicely that you would not die but never sing again.’

‘I would rather die!’ she says.

‘Well, that’s rather the point,’ he says. He moves the sword up to her neck.

‘But what’s to lose?’ he says. ‘If I kill you, I kill you. A risk I shall take. Perhaps a pressure here.’ He pushes the sword in under her chin and she cries out in pain.

‘Yes! The base of the tongue. That should do it! Indeed, yes!’ She screams as the needle blade pierces her flesh, screams up at the blank-eyed mask above her. Warm blood covers her chest, the tip of the sword feels so unnatural, so unwelcome in her throat.

A plunk on the back of the white silk glove. A raindrop.

The rain comes in across the torchlight, great golden berries from the dark sky pattering the leaves and the mould. A conster- nation among the gentlemen – silk may be ruined, lace muddied and, worse, those who had stinted on expense in ribbons, pleats and hats might see colours run, exposing them as cheapskates. ‘My God,’ says Three Fingers. ‘This coat is by Boileau of St-Germain!’

The rain in an instant is a wash, a descending veil.

He draws back his sword hand but then puts his free hand up before his eyes. The white glove is stained with the purple dye of his head ribbon.

‘I’ll kill that haberdasher,’ he says. ‘A cape, gods, a cape!’ He turns away and rushes for his coach.

She spits at him, spits blood.

‘You will go to Hell for this!’ she says, the words agony, bubbling with blood. ‘This is not my final scene!’

She is right. It is, however, the end of her first scene as a kick from God knows where sends her reeling into darkness as the curtain of the rain falls.

The Devil’s Blade is available to pre-order now. Get it here.