The Kindness of Apple Pie

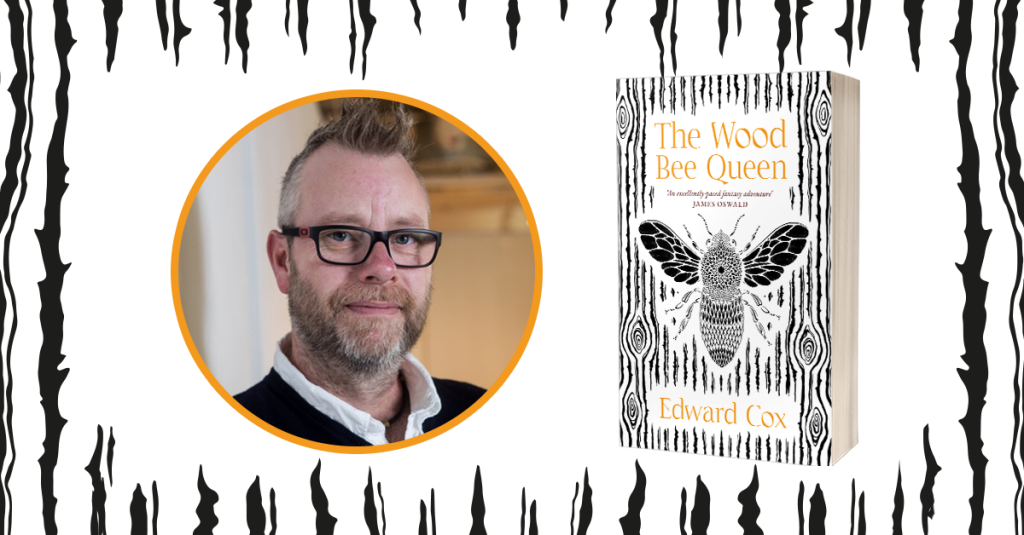

To celebrate The Wood Bee Queen publishing today, here’s a little note from author Edward Cox:

I’m proud to say that Gollancz publishes The Wood Bee Queen today, and this marks the end of over two years of hard work – writing, redrafting, a couple of rounds of edits, proofreading, promoting, and all the other things that occur when bringing a book into existence. It’s a long and detailed process that requires the help of many fine people who ensure that nothing is missed and everything is in place by publication day. So naturally, the moment the book was sent off to the printers was also the moment that the author remembered he’d forgotten to write an acknowledgments page.

Oops . . .

I am the only one to blame for this, but I can and will make amends to the people who deserve due credit. However, I did remember to include a dedication to a very special person, and I’d like to tell you about her.

I was born in the East End of London, where I lived until Christmas 1979 when I was eight years old. I never knew my grandmothers very well; my mum’s mum passed away when I was four or five, and my single memory of her is the toy she gave me as a gift. My dad has never been particularly close to his family, so I didn’t really get to know his mum at all. But a few doors down from our house lived an elderly Welshwoman called Elsie.

Imagine Elsie as my memory recalls her: small. A mop of black curls on her head, etched with grey.A slightly gaunt face, age-lined. Kind and welcoming eyes, and a bright smile whenever she saw you. Every family has a close friend who becomes an honorary aunt or uncle, brother or sister. I think of Elsie as my honorary grandmother.

I always seemed to be visiting her house, where I was of no help whatsoever while she did her housework. I was just happy to be there, to sit and watch and talk. And we talked a lot. Though thinking about it now, I probably did more listening while she did most of the talking. Elsie taught me to count to ten in Welsh: un, dau, tri, pedwar – that’s as far as I can remember. She’d feed me scones or crumpets with cups of tea, as long as I promised not to tell my mum; she didn’t want to get into trouble for me not being able to eat my dinner.

Elsie would tell me stories, mostly about her life and experiences, which always seemed so worldly wise. These stories were often tragic, occasionally grim and frightening, though her intent was to teach not to scare. She wanted me to understand why it was better to be kind, always. And Elsie was full of kindness. Tolerance, too. A genuine positive influence on my early years. But there was also a touch of sadness that hung over her, especially when she told her stories, one of which stands out in my memory more than the others.

Elsie was the go-to babysitter for me and my brother and my sister. She could tuck me into bed so tightly that I couldn’t move an inch. I found this funny and would laugh, thinking she was trapping me so I wouldn’t keep getting up and following her downstairs. I was prone to being a pain in the arse at that age, so there’s probably some truth to this. However, I found it even funnier when Elsie said that what she had done to me was called an Apple Pie. It sounded silly. Apple pie? It didn’t make any sense to me, until the night Elsie explained where the term came from.

You see, during World War II, Elsie had been a nurse. She cared for the injured soldiers sent home from the battlefield. And there were a lot of them. Some had been injured so badly that it was important they didn’t move. The nurses used the Apple Pie technique to keep them still in their beds. I appreciate now that there are different versions of the Apple Pie, one of which is considered a practical joke. But this version was no joke; it could literally save lives. Though Elsie was quick to add that many of these soldiers carried wounds so grievous they never recovered; that as soon as the patients were brought home from the war, she and her fellow nurses were able to tell from their wounds who was not long for this world, no matter what was done.

Elsie told me her story with a soft and sad tone, her eyes drifting away as if seeing the face of every solider she couldn’t help, who had slipped away and out of her care. That’s how I remember it, while lying there in an Apple Pie of my own. She told me the nurses stayed by the sides of every solider, no matter their condition, a constant vigil of light during a long darkness on planet Earth. It was a duty more than a job, one that made her proud and heartbroken. She had lived with the unkindness of war; she had seen what greed and hate and prejudice had done to world. She wanted better for me, and I should want better for mychildren.

Elsie never had children of her own. These days, as I trip headfirst into my middle years, I wonder if she had thought of me as her honorary grandson. Her stories gave me an insight into the importance of kindness. And because it had come from her, it felt truer, somehow more real to me than when my parents tried to teach the same thing. Elsie’s storiessank deep and remain with me even now. She was as much a friend and ally as a grandmother.

I remember clearly the last time I saw her. My family was about to move away from London and I was visiting her house, as I always did. Christmas was approaching and Elsie was wrapping presents, telling me who each gift was for, along with stories about their lives. One of the presents in particular caught my eye: a remote controlled American police car. It was a glorious toy, and I felt very jealous of whoever was to receive it. Elsie had told me that my greatest present this year would be the gift of living in a new house, away from all the dirt and noise of London; and it was in that moment that I realised she wasn’t coming with me. I asked if I would ever see her again, and I recall her keeping her back to me when she answered softly, “I hope so.”

My family swapped red brick and grey concrete for fine, green countryside just in time for Christmas 1979. On Christmas Day, I discovered a surprise among my presents beneath the tree. A gift from Elsie. But not just any gift. A glorious remote controlled American police car, blue and white, with flashing red lights and an engine that made the same nerve-shredding noise as a food disposal. I couldn’t believe she’d remembered. I was amazed that her gift had followed me from London without my noticing. It felt like magic. I was quickly on the phone to Elsie, wishing her a Merry Christmas, thanking her for my surprise.

The larger part of that conversation is now lost to my memory, but our parting words are fixed in my brain. Elsie asked me for one thing. She asked for a promise that I would never forget her. At the time, I didn’t really understand why she wanted this; I was eight and my world was small. I didn’t know much but I knew people couldn’t forget people, especially the ones they loved, right? Her request was a given, it was already in place, and I told her so. That was the last time we ever spoke.

Of course, I understand now that she was asking because children grow up. Our priorities change, our knowledge expands, and many of our childhood memories can fade and rust into forgetfulness. But here’s the thing: I only need to hear the word Walesand I think of Elsie teaching me to count in Welsh. When we clapped on our doorsteps for the hard and tireless work of NHS workers, I was thinking of Elsie. When my daughter was little and I endorsed the Apple Pie technique in the vain hopes that she might stay in bed, I thought of Elsie. When I wrote The Wood Bee Queen, I knew straight away that the character Mai could be none other than the embodiment of my memories of Elsie, her kindness, her spirit, her stories. This is why my book is dedicated to her. I remembered my promise. I never forgot.

And now to make amends to those I did forget by remembering my superdude agents, Howard Morhaim and Caspian Dennis, who are always in the background looking out for me. My cool, calm and collected editor Marcus Gipps, without whom this book wouldn’t exist. Will O’Mullane and Lucy Cameron for their patience with my never-ending emails. And the rest of Mighty Team Gollancz – recently award winning and rightly so! The talented Sue Gent who gave me such a beautiful cover. Paul Stark for supporting the audiobook, and the amazing Beth Eyre whose acting skills brought my story to life. To Lisa Rogers, the Queen of copyeditors, I say: my tall tales always stand taller after spending time with you.

There are the fine authors who took the time to read early proofs and say kind words about the story: Paul Cornell, Joanne Harris, Gavin G Smith, Adrian Tchaikovsky, James Bennett, James Oswald, Miles Cameron, Mark Stay and Stephen Aryan. The reviewers and bloggers who supported The Wood Bee Queen – so many of you, like Nils and Beth. Thank you, thank you, thank you! And to readers everywhere: without you, we authors would be dead in the water.

It has been a tough year for us all, and I’ve had my share of personal problems added to the mix. In this, I’ve been lucky to have a support group of magnificent reprobates: Tade Thompson, Gavin G Smith and R.J. Barker, fine authors and wonderful fellows with whom I shared so many laughs when I was stuck in my own head (Tade, you’re still wrong about Thor’s axe, which makes Gav right, and that just disappoints me and R.J.). And then there’s wise and kind Gillian Redfearn who took the time to ask, “How are you?” Lastly, most importantly, to my wife and daughter, Jack and Marney: We’re stronger together and I love you more than anything.

I forgot to include some well-deserved applause in my book, but I give it to these fine and excellent folk now with great respect and affection. Thank you, one and all.

The Wood Bee Queen is out now in paperback, eBook and audiobook.